For many years therapists have shied away from treating clients who suffer from severe personality disorders. In fact, many health insurance companies will deny reimbursement for treating Axis II disorders (Kersting, 2004). Yet, what happens when a parent with a personality disorder fears losing his or her children in a high conflict custody battle? How does that parent cope? According to the literature, many of these vulnerable parents commonly resort to using primitive defenses such as denial, projection, idealization, devaluation, and splitting (Bernet et al., 2017; Gordon et al., 2008; Kopetski, 1998). Continue reading “Issues in Diagnosing Parental Alienation”

Author: Shawn Wygant, MA, TLLP

Attribution Bias

We at PsychLaw.net teach that Attribution theory examines how we seek to explain people’s behavior[1]. We typically attribute the causes of behavior to internal events (the person’s personality) or external events (the situation in which people find themselves). When explaining their own behavior ‑ or the behavior of someone with whom they identify sympathetically people usually invoke considerations of external events. When assessing the behavior of others however, people characteristically rely on internal events. Asked why Americans defected to the Soviet Union, for example, 80% of a sample of American college students explained the defections on the basis of internal events or personality factors. The students described the defectors’ personalities as “confused, ungrateful, or traitorous.” When asked why Russians defected to the U.S., however, 90% of the students attributed those defections to the oppressive conditions of the Soviet Union[2]. Continue reading “Attribution Bias”

Anchoring Biases of Mental Health Professionals

Mental health professionals typically reach judgmental conclusions very early in their interviews; and then, they cling to those impressions even when confronted with contrary evidence. At PsychLaw.net we consider, for example, a 1964 experiment done by Jerome Bruner at Harvard University[1]. In this experiment, one group of participants (the control group) viewed slightly blurred slides. Nevertheless, the control group participants could identify the objects on the slides with a relatively high degree of accuracy. For the other group of participants (the experimental group), the slides were initially so blurry, subjects could not accurately identify the objects. The experimental group then saw the slides again at a level of clarity equal to what the subjects in the control group saw. At equal levels of clarity, the experimental participants committed a significantly greater number of identification errors compared to the control group. Why did the experimental group commit this greater frequency of errors? Continue reading

Selective Recall of Mental Health Processionals

At PsychLaw.net we know that the expectations of mental health professionals can lead them to believe that symptoms consistent with their diagnostic impressions were exhibited in an interview; when in fact, they were not. Conversely, they are also less likely to recall symptoms that were actually present during an interview but inconsistent with their diagnostic impressions.

These effects of selective memory were dramatically demonstrated in a 1979 experiment using college students. The students read a story about a woman who exhibited both introverted and extroverted traits. Two days later, half of the students were asked to assess how well this woman would do in a sales position ‑ a presumably extroverted career. Continue reading “Selective Recall of Mental Health Processionals”

Research vs. Clinical Judgment

The recent case of People v. Banks[1] in New York demonstrates that reliance on “clinical judgment” is like “shooting from the hip”. Banks found trial judge Barbara Zambelli working her way through a complicated explication of clinical judgment and research based opinions. Banks is instructive because it involved a pitched battle over expert testimony regarding eyewitness identification and 1) the low correlation between a witness’s confidence and the accuracy of the witness’s identification; 2) the effect of post event information on accuracy of identification; and 3) research concerning the eyewitness identification phenomena of stress, partial disguise, own-race bias, and weapons focus. Here, we at PsychLaw.net find that expert Steven Penrod and his examiners made it clear that although there was a great deal of anecdotal information on these phenomena, Penrod was relying on research, not “clinical judgment”. Continue reading “Research vs. Clinical Judgment”

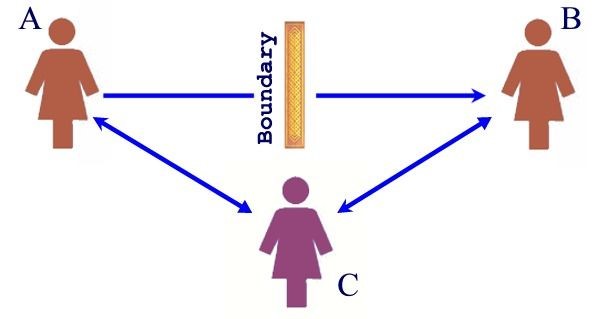

Psychotherapy and Triangulated Relationships

At PsychLaw.net we understand that when psychotherapists join with custodial parents as sympathetic allies, they can find themselves inducted into a perniciously triangulated relationship of “victim”, “villain” and “savior”. Instead of disrupting these triangulated dynamics, therapists too often participate in them. They endorse the custodial parent’s assessment of who the “villain” is, re‑define the custodial parent as a “victim” in addition to the children, and appoint themselves as “saviors” to protect these “victims” from the alleged malevolence of supposed “villains”. Continue reading “Psychotherapy and Triangulated Relationships”

Effective Psychotherapy for Children of Divorce

We at PsychLaw.net feel that when psychotherapists respond effectively to children of divorce, they neither volunteer themselves ‑ nor accept induction ‑ as saviors. Therapists who commit these errors sacrifice their objectivity; and this sacrifice usually leads them into situations where they are more a part of the problem than its solution. Effective psychotherapy for children of divorce requires therapists to reduce the frequency and intensity of parental conflicts. This outcome alleviates the loyalty conflicts which these children often endure; and in turn, the distress that originally necessitated their treatment begins to abate. Continue reading “Effective Psychotherapy for Children of Divorce”

Preconceived Expectations

At PsychLaw.net we consider a 1929 study examined the opinions of 12 interviewers who interviewed 2000 homeless men, attempting to ascertain the reasons for their homelessness.[1] Co‑workers described one of the interviewers as an ardent socialist. By an almost three to one margin, the “socialist” interviewer concluded the homelessness of the men he interviewed reflected economic conditions beyond their control (lay‑offs, plant closings, etc.). Another interviewer was described as a strong prohibitionist. Again by an almost three to one margin, the “prohibitionist” interviewer attributed homelessness to alcohol abuse. While relying on their clinical judgments, these interviewers demonstrated a remarkable facility for finding evidence consistent with their preconceived expectations. Continue reading “Preconceived Expectations”

Ruling In vs. Ruling Out

In response to their own expectations, mental health professionals often ask questions that can only confirm their a priori hypotheses. At PsychLaw.net we know that fundamental considerations of scientific logic, however, dictate that mental health professionals engage in a process known as “proof by disproof.”[1] In other words, a scientific hypothesis is tentatively accepted if, and only if, it cannot be disproven. Scientific experiments, are therefore designed to disprove hypotheses. Similarly, physicians typically reach their diagnostic conclusions attempting to rule out alternative explanations for a condition. Continue reading “Ruling In vs. Ruling Out”

Ethical Standards & Practices in Risk Assessment

At PsychLaw.net we take note that there are no professional standards available that have been specifically developed for the assessment of violence risk.[1] Nevertheless, there are general ethical principles and practice standards applicable to these assessments. Psychologists undertaking risk assessments are obviously obligated to comply with the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct [2] (hereafter referred to as the “Ethical standards”) Continue reading “Ethical Standards & Practices in Risk Assessment”

Relevant Ethical Codes

At PsychLaw.net we emphasize that the current 2008 Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social Workers clearly prohibits social workers from practicing outside their area of competence. In particular, Standard 1.04 (a), addressing “Competence,” states:

“Social workers should provide services and represent themselves as competent only within the boundaries of their education, training, license, certification, consultation received, supervised experience, or other relevant professional experience.”[1] Continue reading “Relevant Ethical Codes”

Dual Relationships and Ethical Obligations

Dual relationships inevitably involve conflicts of interest. Just as an attorney cannot represent the business interests of a client in one matter, and also represent that client’s spouse in a divorce action, mental health professionals are prohibited from engaging in similar conflicts of interest. At PsychLaw.net, we consider dual relationships problematic and unethical. This is clearly articulated in the various ethical codes. Take for example Standard 1.06 (c) of the Code of Ethics for social workers which states: Continue reading “Dual Relationships and Ethical Obligations”

The “Wonderfully Stupid” Expert Admissibility Tests

The Emphasis at PsychLaw.net is that to move the law of expert testimony forward, the cross examiner must be cognizant of these decent tests, but must be aware of the terrible tests for expert qualification as well. Faced with many draconian decisions, attorneys tend to develop a compensating sense of “gallows humor”. With our respect to all those cross examiners who have to endure the sometimes ridiculous and heartbreaking decisions of our trial and appellate courts, we have begun to collect what we refer to as the “wonderfully stupid” expert admissibility tests. Continue reading “The “Wonderfully Stupid” Expert Admissibility Tests”

Who Qualifies as An Expert?

Federal Rule of Evidence 702 states: “If scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will assist the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue, a witness qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education, may testify thereto in the form of an opinion or otherwise.”[1] At PsychLaw.net we remember that because it carries such an “aura of infallibility,” [2] scientific testimony can create difficult problems for our courts. Summarizing the literature, one respected commentator has written: “[t]here is virtual unanimity among courts and commentators that evidence perceived by jurors to be ‘scientific’ in nature will have particularly, persuasive effect.”[3] Continue reading “Who Qualifies as An Expert?”

DAUBERT HEARINGS

Federal Rule of Evidence 104(a) provides that preliminary questions concerning the qualification of a person to be a witness, or the admissibility of evidence, shall be determined by the court. Federal Rule of Evidence 104 (c) provides in part that hearings on preliminary matters may be conducted when the interests of justice require. FRE 104 (a) authorizes a court to hold an evidentiary hearing to make a preliminary determination that the expert is properly qualified, and that the expert’s underlying reasoning or methodology is scientifically valid and properly can be applied to the facts of the case.[1] In the exercise of its gatekeeping function, the Daubert Court held that a trial court must undertake a preliminary determination of whether the methodology of the expert’s proposed testimony is scientifically reliable. Continue reading “DAUBERT HEARINGS”

The Move Toward “Validity” and “Reliability” in the Courts

After seventy years of service, Frye v United States, 54 US App D C 46, 293 F 1013 (1923) and the “generally accepted in the scientific community” analysis for admissibility of scientific testimony, began to create some silly results. At PsychLaw.net we know that as recently as the early 1990’s, attorneys and “experts” too often succeeded in manipulating the “general acceptance” admissibility rules. As a result, all sorts of “science” began to find its way into the courts. Continue reading “The Move Toward “Validity” and “Reliability” in the Courts”

Psychologists in Pursuit of Market Share

What accounts for astounding frequency with which mental health professionals betray our courts with misinformation premised on ill-conceived theories? At PsychLaw.net we consider, for example, the direction taken by practicing psychologists over the past 20 years. Beginning in the late 1970’s, the number of independently practicing psychologists belonging to the American Psychological Association (APA) grew at an exponential rate. These practitioners demanded that APA respond to issues such as insurance reimbursement, hospital privileges, and the wholesale promotion of psychological services. Continue reading “Psychologists in Pursuit of Market Share”